Friday, August 16, 2013

The next HPNA Boston meeting

Date: Wednesday, September 25

Time: 5:30PM registration and complementary food/beverages, 6:00PM program start

Topic: "Medical Marijuana - the newest green state is seeing red."

Place: Hospice of the Good Shepherd, 90 Wells Ave. Newton MA

Cost: Free for HPNA Boston members; $10 non-members; fee waived for student nurses

This program has been approved for 1.5 contact hours.

View Larger Map

Thanks to Pelham Community Pharmacy for their generous support of this meeting.

Smoke 'em if ya got 'em.

Sunday, May 5, 2013

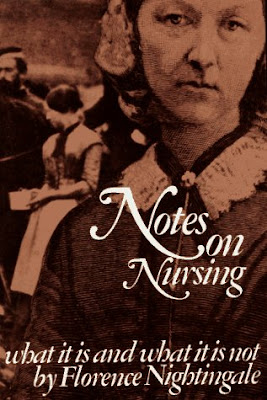

Celebrate nurses day/week/month

"...nursing ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet — all at the least expense of vital power to the patient."

Friday, April 5, 2013

Monday, March 25, 2013

Choosing the path

Two Paths Through Pines

photograph by Mark A. Kawell

I’ve developed several metaphors that have proven helpful when talking to families facing catastrophic injury/illness and the possibility of death, and who need to understand end of life care in a meaningful context.

First, let's stop using the awful expression “withdrawing care.” None of us would feel comfortable taking something away from a loved one, especially when that something is literally keeping our loved one alive.

I use the term “redirecting care,” to emphasize our conscious decision to focus on a specific set of objectives – most notably comfort, dignity, and family closeness. This idea also makes better sense when considered in the context of what I describe to families as the three basic paths guiding care in the acute setting.

Curing – The first path focuses on curing the patient’s underlying illness or injury. I use antibiotic therapy and surgery as examples. Often, the patient’s own history includes one or more initial treatments directed at curing, so this is pretty straightforward for most people to understand.

When a patient’s condition is dire, it also helps the family see that the path to a cure may be highly uncertain at best, or even unrealistic, no matter how desperately they may hope otherwise.

Support for Healing – The second path emphasizes actions that support the patient’s own ability to heal. I point to interventions like the nutrition from high calorie/high protein tube feedings, and intubation with mechanical ventilation, as ways that we help a patient get better. I also point out that these measures are generally only needed for a limited time, even if that temporary period extends for weeks.

When a patient hasn’t improved or recovered despite our actions, the family usually finds it easier to understand that the possibility for healing has become more remote.

Comfort and Dignity – The third path is entirely devoted to keeping the patient comfortable in whatever way is required - controling pain, easing air hunger, and calming agitation; and to maintaining the patient’s identity as a person with friends and family who love them.

I also emphasize and identify ways that the family can join in providing this comfort and insuring this dignity.

Families are more at ease when they’re confident we’ll help keep their loved one comfortable, and when they know they’ll all be treated with respect and not left alone.

I’ve found that these three concepts of care support more meaningful discussions with families to determine the most appropriate goals of care. We’re less likely to get into misunderstandings and struggles, and more likely to focus on what we all agree is most important.

I use the term “redirecting care,” to emphasize our conscious decision to focus on a specific set of objectives – most notably comfort, dignity, and family closeness. This idea also makes better sense when considered in the context of what I describe to families as the three basic paths guiding care in the acute setting.

Curing – The first path focuses on curing the patient’s underlying illness or injury. I use antibiotic therapy and surgery as examples. Often, the patient’s own history includes one or more initial treatments directed at curing, so this is pretty straightforward for most people to understand.

When a patient’s condition is dire, it also helps the family see that the path to a cure may be highly uncertain at best, or even unrealistic, no matter how desperately they may hope otherwise.

Support for Healing – The second path emphasizes actions that support the patient’s own ability to heal. I point to interventions like the nutrition from high calorie/high protein tube feedings, and intubation with mechanical ventilation, as ways that we help a patient get better. I also point out that these measures are generally only needed for a limited time, even if that temporary period extends for weeks.

When a patient hasn’t improved or recovered despite our actions, the family usually finds it easier to understand that the possibility for healing has become more remote.

Comfort and Dignity – The third path is entirely devoted to keeping the patient comfortable in whatever way is required - controling pain, easing air hunger, and calming agitation; and to maintaining the patient’s identity as a person with friends and family who love them.

I also emphasize and identify ways that the family can join in providing this comfort and insuring this dignity.

Families are more at ease when they’re confident we’ll help keep their loved one comfortable, and when they know they’ll all be treated with respect and not left alone.

I’ve found that these three concepts of care support more meaningful discussions with families to determine the most appropriate goals of care. We’re less likely to get into misunderstandings and struggles, and more likely to focus on what we all agree is most important.

- - - - -

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Captain Obvious comes right back

"My job is obviously never done."

I was researching back issues of the HPNA journal for an upcoming class on assessing and managing pain when our friend Captain Obvious stuck out his size-13 black boot and tripped me right in front of an article by Ann Marie Dose and colleagues, "The Experience of Transition From Hospital to Home Hospice - Unexpected Disruption."

As Captain Obvious pointed out earlier, while we may take much for granted in the course of our work, our patients and families are experiencing each element of the hospice admission and care for the first time, most often with little preparation, understanding, or context; and always with some degree of emotional stress. Our routine is their disruption.

The authors note:

"Many patients hospitalized at end of life report ‘‘going home’’ as the most important task remaining to achieve. In order to meet this meaningful goal, patients in this study were discharged soon after the decision was made to go home with hospice care.

Although the physical act of traveling home was relatively problem-free for the study participants, family caregivers experienced burden as a result of getting things ready for the patient’s homecoming often on very short notice. (for example) While securing a hospital bed for the home may be of little consequence for healthcare professionals...for patients and family caregivers, the hospital bed took on a larger meaning and added to the overall disruption."

I'm reminded of an old joke that goes something like this -

Q - What are the two differing points of view with regards to a ham and egg breakfast?

A - The chicken has an interest, but the pig is committed.

to learn more - Dose, Ann Marie PhD, RN, ACNS-BC; Rhudy, Lori M. PhD, RN; Holland, Diane E. PhD, RN; Olson, Marianne E. PhD, RN. The Experience of Transition From Hospital to Home Hospice: Unexpected Disruption. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing: November/December 2011 - Volume 13 - Issue 6 - pp 394-402.

Monday, March 18, 2013

Meet Captain Obvious

Ya think?

We're happy to introduce a new contributor to the HPNA Boston blog. Captain Obvious will join us on a semi-regular basis to point out things we already know, or should. Because a little review never hurt anybody, right?

In today's installment, Captain Obvious says:

We're hospice professionals. We take our work seriously. We draw on our accumulated knowledge and experience, as well as that of our colleagues, teams, agencies, and professional resources like HPNA. In the course of our practive we've likely encountered just about every possible situation at least once. And when we run into something new, chances are we know exactly who to turn to for help.

We anticipate and prevent problems. We're experts at assessing and addressing pain, delirium, nausea, constipation, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, and more. We can calculate the equianalgesic doses of multiple opioids. We know when to stop a measure that's not working, and have backup plans for just such instances.

We know how essential are our colleagues in chaplaincy, social work, medicine, music therapy, bereavement, and volunteer services. We help get them through the door when families are reluctant or unsure about meeting them.

We work in settings of abject poverty one moment, and unimaginable wealth the next.

We've sat with patients as they've drawn their last breath, and with their families in the days leading up to, and following, that moment. We've been present for the unique beauty of a peaceful death, as well as the despair of a distressing one.

In the most difficult cases or during the most trying moments, we're in the home for an hour or two out of every 24.

The greatest challenge of our work is teaching those family members, friends, and others in the home all of the hours in a day, to become as expert as we are, but in a much shorter time, with much less preparation, fewer resources, even less context, and often under tremendous emotional pressure.

And they only get to do it once.

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Where to sit?

Sean O’Mahony, a palliative care doctor,

with a patient, Deborah Migliore, in the Bronx.

with a patient, Deborah Migliore, in the Bronx.

Photo - James Estrin/The New York Times

I came across the piece accompanying this photo in a recent issue of the New York Times. It's titled, "At the End, Offering Not a Cure but Comfort." It's the third in the series, "Months to Live." The first, "Fighting for a Last Chance at Life," appeared in May. The second, "Sisters Face Death With Dignity and Reverence," was published in July. (free registration required for access)

I highly recommend each one, and look forward to future installments.

I was most struck, however, by this reader comment:

I don't know if the picture at the top of the first page of the article was posed but one thing struck me. The medical personnel are on one side in opposition to the patient. It really made me feel the distance they were maintaining from the patient they were trying to help. Someone could move to sit beside her and perhaps the group dynamics would change and the information exchange would be enhanced. These seem like very caring team members, but little things can make a big difference....It's an astute observation, and prompts a story of my own -

I once took over the care of a patient who was less than 30 years old, after a colleague who was working 7am-3pm left for the day. I've always worked 7am-7pm, and so was going to be with this patient for 4 hours. I had not previously cared for the patient or met any of the patient's family or other visitors.

The patient had experienced prolonged global cerebral anoxia the prior week, and was now suffering from the complication of profound autonomic dysfunction.

While the patient still had some brainstem activity, the overall prognosis was extremely grim, and had been from the beginning.

The patient's parents were divorced, but both had maintained an active presense. An older sibling was also closely involved in directing decisions on the patient's behalf.

A few days after the patient had been admitted, one parent and the sibling had advocated against a tracheostomy (trach) and percutaneous enterogastric (PEG) feeding tube for longer-term respiratory and nutritional support, saying that the patient would not have wanted to be kept alive under such circumstances.

The other parent held out some hope, and wanted to give the patient a chance for recovery, so the decision had been made to proceed with the trach and PEG.

The three family members had also agreed to revisit the patient's goals for care after one week, and that time had now arrived. The hospital's palliative care team had been consulted, and was going to meet with the family later that afternoon.

The parent who had held out the most hope was in the room when I took over, accompanied by a supportive sibling. They both sat to one side of the bed.

The attending physician and fellow from the palliative care team arrived at about the same time I did. I joined them as they entered the room to introduce themselves.

The parent wanted to wait until the patient's older sibling arrived before beginning any discussion, and anticipated that it would be at least another hour. The parent's demeanor was very guarded, almost angry. The two physicians gave me their pager numbers, and as they left I agreed to contact them when the sibling arrived.

There were now four of us in the room - the patient, the parent, the parent's own supportive sibling, and me. It was suddenly very still and quiet. I was the only one standing.

I felt a sob well up in my chest. I don't know why, exactly - maybe it was because the patient was not much older than my own two children, or because the parent looked so sad and lost.

I managed to stifle the worst of the sob, but it was all I could do to look at the parent's tear-filled eyes and simply choke out, "I'm so, so sorry."

I really meant it. There was nothing else that I could do or say. The parent nodded.

Then I squatted down besides the parent's chair. There was no other place for me to sit. We were all now looking in the same direction, towards the patient lying just above the level of our eyes in the bed several feet away.

A minute or two passed without a word, then the parent started to talk.

There's much more to the story, certainly. But the point I wanted to make, the point that was prompted by the reader comment, was simply that sometimes it's so important to sit next to somebody in order to actually be with them.

- - -

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Poetry as reflection

Philippe Petit walks a tightrope

between the twin towers of the World Trade Center

August 7, 1974

Air

by W.S. Merwin

Naturally it is night.

Under the overturned lute with its

One string I am going my way

Which has a strange sound.

Under the overturned lute with its

One string I am going my way

Which has a strange sound.

This way the dust, that way the dust.

I listen to both sides

But I keep right on.

I remember the leaves sitting in judgment

And then winter.

I listen to both sides

But I keep right on.

I remember the leaves sitting in judgment

And then winter.

I remember the rain with its bundle of roads.

The rain taking all its roads.

Nowhere.

The rain taking all its roads.

Nowhere.

Young as I am, old as I am,

I forget tomorrow, the blind man.

I forget the life among the buried windows.

The eyes in the curtains.

The wall

Growing through the immortelles.

I forget silence

The owner of the smile.

I forget the life among the buried windows.

The eyes in the curtains.

The wall

Growing through the immortelles.

I forget silence

The owner of the smile.

This must be what I wanted to be doing,

Walking at night between the two deserts,

Singing.

Walking at night between the two deserts,

Singing.

---

Chaplains at several of the hospice agencies where I've worked often open team meeting with a poem or similar reading, as a way to help us slow down our thoughts and reflect upon what we do. I like the tradition.

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

MOLST, and more

Julie Bushey provided a comprehensive history at last week’s chapter meeting on the development of the new Massachusetts Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) form. Julie is chairperson of the palliative care committee at her hospital, and described how she is co-directing their plans to adopt MOLST by mid-April.

Julie noted MOLST is based on the ‘POLST paradigm.’ POLST is the acronym for Physician/Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, which attempts to help patients more fully articulate their end of life wishes beyond the simple ‘do not resuscitate’ order clinicians are currently familiar with.

MOLST enhances the two basic choices patients currently have regarding goals of care - the DNR (do not resuscitate with cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or intubation/artificial ventilation), by providing the opportunity to indicate their wishes regarding additional options: intubation and artificial ventilation for a limited time; noninvasive ventilation assistance, such as with C-PAP; hemodialysis; artificial nutrition and hydration; and transfer to a hospital. There is also space for other measures not directly addressed on the form, such as antibiotic therapy.

MOLST is intended for patients facing potentially life-limiting events, such as a diagnosis of advanced cancer, progressive disease, trauma, or other acute event. In completing the form, the patient and clinician affirm they have discussed goals of care.

I found Julie’s presentation, and the discussion it generated, useful. But at the same time, the experience emphasized how even this latest attempt to encourage honest discussion between patient, family, and clinicians still falls far short of the ideal. It seems to me the greatest risk with MOLST and the tools which preceded it, is that the discussion often lacks meaningful context.

In other words, we can help patients and families fill out a form, but that’s not nearly enough. We risk ending up with a simple shopping list, when we really need to understand much more.

I think our patients and families are much better served if we also consider, internalize, and use a simple set of 4 questions developed by Susan Block to guide our initial and ongoing conversations about goals for care at end of life:

1. What do you know about your prognosis?

2. What are your fears?

3. How do you want to spend your time?

4. How much suffering would you be willing to endure, if it offered the possibility of more time?

The actual wording of each of these questions will vary, depending on who it is we’re talking to, and where they are in the overall process of achieving a peaceful acceptance of death. But we can keep the questions as written in mind, as we develop our skills in guiding conversations about goals of care at end of life.

Put another way - if you understand your patients and families based on their answers to Susan’s 4 simple questions, you’ll have much more than a signed form to guide the care they really want and need.

Here’s Atul Gawande speaking to Susan’s questions at the 2010 New Yorker Festival:

Julie noted MOLST is based on the ‘POLST paradigm.’ POLST is the acronym for Physician/Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, which attempts to help patients more fully articulate their end of life wishes beyond the simple ‘do not resuscitate’ order clinicians are currently familiar with.

MOLST enhances the two basic choices patients currently have regarding goals of care - the DNR (do not resuscitate with cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or intubation/artificial ventilation), by providing the opportunity to indicate their wishes regarding additional options: intubation and artificial ventilation for a limited time; noninvasive ventilation assistance, such as with C-PAP; hemodialysis; artificial nutrition and hydration; and transfer to a hospital. There is also space for other measures not directly addressed on the form, such as antibiotic therapy.

MOLST is intended for patients facing potentially life-limiting events, such as a diagnosis of advanced cancer, progressive disease, trauma, or other acute event. In completing the form, the patient and clinician affirm they have discussed goals of care.

I found Julie’s presentation, and the discussion it generated, useful. But at the same time, the experience emphasized how even this latest attempt to encourage honest discussion between patient, family, and clinicians still falls far short of the ideal. It seems to me the greatest risk with MOLST and the tools which preceded it, is that the discussion often lacks meaningful context.

In other words, we can help patients and families fill out a form, but that’s not nearly enough. We risk ending up with a simple shopping list, when we really need to understand much more.

I think our patients and families are much better served if we also consider, internalize, and use a simple set of 4 questions developed by Susan Block to guide our initial and ongoing conversations about goals for care at end of life:

1. What do you know about your prognosis?

2. What are your fears?

3. How do you want to spend your time?

4. How much suffering would you be willing to endure, if it offered the possibility of more time?

The actual wording of each of these questions will vary, depending on who it is we’re talking to, and where they are in the overall process of achieving a peaceful acceptance of death. But we can keep the questions as written in mind, as we develop our skills in guiding conversations about goals of care at end of life.

Put another way - if you understand your patients and families based on their answers to Susan’s 4 simple questions, you’ll have much more than a signed form to guide the care they really want and need.

Here’s Atul Gawande speaking to Susan’s questions at the 2010 New Yorker Festival:

Thursday, February 28, 2013

New member benefit

Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association (HPNA) members now have full access to CE credits for free.

Over 40 online courses are immediately available within the HPNA E-Learning site.Additional courses are being developed. HPNA is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation (ANCC).

HPNA members enjoy:

-Online courses with approved CE credit at no cost

-Free CE Tracking

-Unlimited Access to HPNA's most popular courses, including Opioids in Palliative Care, The Picture of Heart Failure, and Pain Management for all Ages.

Visit HPNA to join.

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Observing a birthday

Steven Paul 'Steve' Jobs

February 24, 1955 - October 5, 2011

His 2005 commencement address at Stanford. Offered without further comment.

Saturday, February 23, 2013

Getting the toboggan

Toboggan return to toboggan tow at base of hill.

Caberfae Winter Sports Area. 1940-1941.

(source)

Caberfae Winter Sports Area. 1940-1941.

(source)

I sat quietly by his bed as the mid-morning sun shone through the window. The angle of the light transformed the contours of his fresh white sheets into bright flowing hills and deep shaded valleys that mimicked the snowy fields outside.

He was in his late 80’s, and had been slowly declining over the past years. Now, his breathing had settled into the peaceful but irregular pattern of approaching death.

Something had happened since her visit yesterday, when they both sipped coffee and enjoyed his favorite cookies. She informed the eldest son by phone, and he agreed to call his siblings, who lived out of state. “They’ll start arriving in the next few hours. I’ll get the comfort kit set up.”

She reviewed the medication schedule with the private caregiver, 5mg of morphine oral concentrate every four hours, and drew up a small amount of thick pink liquid into each of several syringes. She squirted the first dose gently behind his lower lip, and massaged his gums while reviewing the technique with the caregiver.

That task complete, we sat by the bed without speaking for about ten minutes, until it was time for us to go.

“He loved the snow,” she said when I noted how the distant fields matched the near scene of his bed sheets. “Last week, when I told him about the coming blizzard, he said ‘Let’s get the toboggan ready.’ He just loved the snow.”

He was in his late 80’s, and had been slowly declining over the past years. Now, his breathing had settled into the peaceful but irregular pattern of approaching death.

Something had happened since her visit yesterday, when they both sipped coffee and enjoyed his favorite cookies. She informed the eldest son by phone, and he agreed to call his siblings, who lived out of state. “They’ll start arriving in the next few hours. I’ll get the comfort kit set up.”

She reviewed the medication schedule with the private caregiver, 5mg of morphine oral concentrate every four hours, and drew up a small amount of thick pink liquid into each of several syringes. She squirted the first dose gently behind his lower lip, and massaged his gums while reviewing the technique with the caregiver.

That task complete, we sat by the bed without speaking for about ten minutes, until it was time for us to go.

“He loved the snow,” she said when I noted how the distant fields matched the near scene of his bed sheets. “Last week, when I told him about the coming blizzard, he said ‘Let’s get the toboggan ready.’ He just loved the snow.”

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Our weekly laugh at/with death.

Photo: Sylvain Gaboury/Film Magic

from New York magazine

from New York magazine

Paul Rudnick is a funny guy. He writes regularly for the New Yorker magazine, often contributing to the weekly humor column, 'Shouts and Murmurs,' which is where I generally encounter his work. He's also written several plays and movie screenplays.

I just finished his latest book, I Shudder: And Other Reactions to Life, Death, and New Jersey.

Here's what I know about death and grieving: None of it makes any sense, although I will always cherish the words of a woman who spoke at a friend's memorial, and who began her affectionate remarks by saying, "God knows, Ed was cheap." Here's what I know about New Jersey: If you're a citizen, be proud of it. I know a guy from Piscataway who would tell people that he was from the more posh Princeton, which was forty-five minutes away. I always wanted to tell him, Darling, you're still from New Jersey. Who are you kidding?originally posted at my personal blog in 2010.

And here's what I know about love: Don't let go.

Saturday, February 16, 2013

Safety on the road

Relative risks of an accident based on activity while driving

(based on data by the National safety Council)

*texting includes dialing, looking up email/phone number,

or any other cell phone activity with visual distraction > 3 seconds

How dangerous can it be, to be a hospice care provider?

By “dangerous,” I mean hazardous to the health and safety of the hospice nurse, social worker, chaplain, or hospice aide providing care to patients and families in their homes, or at facilities.

According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) at the U.S. Department of Labor, and others, the answer may surprise you. We work in an industry, specifically the home health care subsector, which poses significant ongoing risks to us for serious illness, injury, and death.

I only recently began to appreciate the scope and severity of these dangers, as I researched the topic to prepare an orientation class at my agency. Maybe I didn’t already understand the risks because I didn’t listen closely during my own orientation, or perhaps the topic wasn’t presented effectively.

The potential for serious bodily harm, or even death, merits our undivided attention. Let’s look at just one of the dangers we face, namely driving to and from the places we visit and give care.

A study conducted by BLS between 1995 and 2004 reported 154 job-related deaths among home care paraprofessionals - nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides. The majority of these deaths resulted from motor-vehicle accidents.

Research conducted on behalf of the National Association for Home Care and Hospice (NAHC) found that home care and hospice workers in the U.S. drove almost five billion (5,000,000,000) miles in 2006, to provide four hundred and twenty-eight million (428,000,000) visits to nearly 12 million patients.

The NAHC study showed Massachusetts home care and hospice workers drove 77,737,289 miles to conduct 13,182,930 visits that year – an average of 6 miles per visit in this relatively small and densely-populated state.

Take a moment to consider the time and distance associated with your own work-related travel in the course of a normal week. Better yet, consider how you drive during those trips, and what other tasks you try to accomplish behind the wheel – particularly those that involve your cell phone.

Work by the National Safety Council (pdf), and by researchers at the University of Utah (pdf), and the American Automobile Association (pdf), among others, concludes that driving while talking on a cell phone increases the risk of an accident at least four-fold, equivalent to the risk of driving drunk.

The researchers find it makes no difference whether we hold our cell phones while talking and driving, or use a ‘hands-free’ device like a speaker phone or Bluetooth earpiece/microphone (pdf). The problem is one of simple neuroscience – our brains are not wired to do two things at the same time.

Driving a car is a complex cognitive task, no matter how routine is may seem. Conducting a conversation is just as challenging when the rich mix of subtle nonverbal cues we depend on while taking face to face is absent.

The brain can switch between the two tasks, but it can’t do both at the same time. In other words, multitasking is a myth (pdf), at least when it comes to people.

More complex cell phone tasks pose an even greater hazard, and increase accident risk by over twenty times, because looking up a phone number, checking an email, or texting diverts visual attention. Lots can happen in the distance covered in just three seconds at 55 miles per hour.

There were 33,808 deaths attributed to automobile accidents in the U.S. in 2009 (pdf). Sixteen percent of those deaths – 5,474 to be exact – were caused by distracted driving, which includes cell phone use.

The National Safety Council is actively working for laws banning cell phone use while driving. They’ve also established four simple ways to increase driving safety:

1. wear your seat belt

2. drive sober

3. focus on the road

4. drive defensively

We’re on the road because we’re committed to helping our patients and families achieve the optimal outcome of hospice care - a peaceful death.

It’s frightening to contemplate how our actions while driving could instead result in another family’s sudden and traumatic loss. Perhaps even our own.

by Jerry Soucy, RN, BSN, CSS, CHPN

An edited version of this piece appeared in the HPNA Boston Winter 2013 newsletter

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

A movie for hospice (French, subtitles)

My wife and I go to the movies several times each month. There are several local independent theaters to choose from, including our favorite – the six-screen West Newton Cinema.

I pay close attention to how movies treat end of life, and have never seen aging and death portrayed with such understated power and honesty as in ‘Amour,’ (‘Love’), the French film by Michael Haneke.

This is the story of Anne and Georges, retired music teachers living in Paris. Anne suffers a stroke that leaves her right side paralyzed, and Georges cares for her, mostly alone.

All of the action takes place within their apartment. It’s not possible to know how much time passes as Anne declines, but any hospice professional will recognize the trajectory.

Each scene is filmed simply, and unfolds without hurry. The dialogue is spare. When their daughter Eva, a musician who lives in London, asks Georges what will happen next as Anne continues to fail, he replies, “Things will go on as they have done up until now. They'll go from bad to worse. Things will go on, and then one day it will all be over.”

That notion, “things will go on,” is what makes ‘Amour’ such a powerful and important film for anybody working in hospice. We visit, but then we leave, and when we leave the patients and families have no alternative but to face each moment as it unfolds. We recognize, even if we don’t clearly say, that “one day it will all be over.”

We also briefly watch each of two nurses who join Georges in helping care for Anne. As in the rest of the movie, every aspect of these encounters is completely credible to anyone familiar with the situations depicted – not as would be portrayed in a documentary, but in the more important and deeper sense of artistic truth.

Because, in the end, ‘Amour’ is a work of art, and only art can touch us so deeply.

More (including trailers)…

Amour at Sony Classic Pictures

Amour at Rotten Tomatoes

Amour at Movie Review Intelligence

Monday, February 11, 2013

February presentation/meeting

HPNA/Boston is hosting a presentation on MOLST - “Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment”

Feb 26 at Newton-Wellesley Hospital Shipley Auditorium, 2nd Floor in the main hospital building. 2014 Washington St Newton, MA

A light dinner will be provided. 5:30-6:00 PM Networking; 6:00 PM MOLST presentation, followed by membership meeting.

Feb 26 at Newton-Wellesley Hospital Shipley Auditorium, 2nd Floor in the main hospital building. 2014 Washington St Newton, MA

A light dinner will be provided. 5:30-6:00 PM Networking; 6:00 PM MOLST presentation, followed by membership meeting.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)